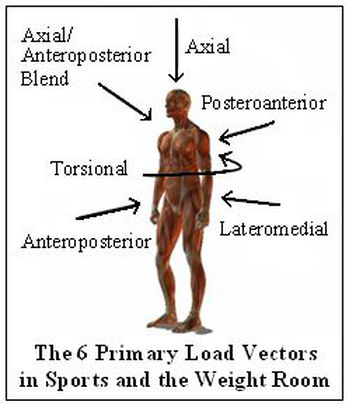

Load or force vector theory was first introduced by the Glute Guy Bret Contreras back in 2010. It involves characterising movement by the direction of resistance as stated in his article HERE. In theory, if we train movements in the same force vector as the sport specific movement, then there should be carry over to improve that movement. For example, Contreras et al. [1] states that the hip since the hip thrust is performed in the anteroposterior force vector (front to back), then it may have better transfer to sports dependent upon horizontal force production (e.g. rugby, sprinting, football) because when standing, horizontal force vectors are anteroposterior (see picture below). In contrast, the squat may have a stronger transfer to the vertical jump due to its axial force vector (top to bottom).

Courtesy of Bret Contreras

Why Are Load Vectors Important To Training?

Why Are Load Vectors Important To Training?

As stated above, force vectors may allow us to enhance our transfer of weight room activities to sporting performance. There are a few papers that demonstrate the importance of load vectors and their association with sports specific training. “Sports specific training” is a term thrown around by coaches but often, load vectors are not taken into account. So is it really sports specific when most of the training program occurs in the axial load vector (squats, olympic lifts etc)?

A new paper by Dello Iacono et al. [2] showed that horizontal drop jumps had an acute effect of potentiating acceleration ability of short distance sprints and change of direction ability in elite handball players. But what about longer term effects? A recent paper by Ramirez-Campillo et al. [3] investigated the effects of vertical and horizontal plyometrics on vertical jump, broad jump, drop jump, bounds and 30m sprint in young soccer players (10-14yrs old) over 6 weeks. The authors found vertical exercises induced significantly greater increase in performance tests in the vertical plane (vertical jump, drop jump). Moreover, horizontal exercises induced significantly greater increase in performance tests in the horizontal plane (broad jump, sprint tests, bounding).

In addition to this, Antonio et al. [4] looked at a 10 week intervention of either vertical or horizontal single leg drop jumps on vertical jump and the 25m shuttle sprint (from this, 10m sprint time and change of direction) in elite handball players. Players performed 5-8 sets x 6-10 reps throughout the intervention. Greater improvements were seen in 10m sprint (8.5% vs 4%) and change of direction on the horizontal group, whereas vertical jump improved more in the vertical group.

Lastly, a recent study by Contreras et al. [1] investigated the effects of a 6 week intervention of hip thrusts vs front squats on vertical jump, broad jump and 20m sprint performance in 24 young (14-17yr old) NZ rugby and rowing athlete development athletes. The authors found the hip thrust group had a greater improvement in broad jump (2.33% vs 1.69%), 10m sprint (-1.06% vs +0.10%) and 20m sprint (-1.70% vs -0.67%). While the vertical jump favoured the front squat group (6.81% vs 3.30%).

Courtesy of YLMSportScience

So What Does This Mean For Your Training?

It seems that it’s not just the total force produced but the orientation of force when performing specific tasks that is of upmost importance [4, 5]. (For more information about this, check out our Agility Ladder Myth article HERE on speed). So take a look at your training program, does it primarily involve exercises that have you loaded axially such as squats, deadlifts, box jumps? Does your sport require you sprint, tackle or block or make contact with an opponent? Do you have to move side to side or rotate often? These are all questions you need to answer when designing your training program for your sport. Martial arts and golf need a high dose of rotational movements (torsional load/force vector), while tennis also needs a lot of lateromedial emphasis. Examples of exercises for each force vector can be found in Bret’s article HERE. So next time you go to train, think about what you are trying to improve. Training just to get strong may not be as beneficial as learning to get strong in the direction you want to apply it.